H.P. Lovecraft had two pet peeves: the dark universe with its malevolently twinkling stars and Earth’s unfathomable oceans. Both were at the time mostly unexplored spaces that provided untold dwelling places for lurking monsters threatening human civilisation.

One of the first stories Lovecraft wrote as an adult, in 1917, was called Dagon. It contains a series of elements that would all return in his later works, and Dagon is considered Lovecraft’s first story that fits into his Cthulhu Mythos. Actually, many believe that The Call of Cthulhu is essentially a reworking of Dagon. What’s it about? A lost sailor lands on a spot that’s part of the seafloor risen to the surface because of volcanic activity. There he finds a monolith with hieroglyphs depicting human-like sea creatures. A monster emerges from the sea to worship at the monolith’s foot and — what else did you expect in a Lovecraft story? — the narrator faints only to reawaken in a San Francisco hospital after being rescued by an American ship. He can’t tell his story to anyone fearing they’d consider him a madman, and his dreams are forever haunted by horrifying visions. Dagon himself doesn’t make an appearance in the story.

Contrary to what he’d do in later stories, Lovecraft didn’t make up a gibberish-sounding name for the terrible deity worshipped at the monolith but picked a name from Sumerian mythology. Since the early 19th century, French archaeologists had been digging in Mesopotamia. Sumer was discovered in 1853 by the British. Although Mesopotamian archaeology never lit up the public imagination like the diggings in Egypt, several authors pricked up their ears. For instance, Agatha Christie visited Ur, Nimrod, and Nineveh in the late 1920s and even married an archaeologist, Max Mallowan, her second husband. Her experiences in Ur led to her 1936 mystery novel Murder in Mesopotamia. So, it isn’t all that surprising that Lovecraft looked to the Middle East for inspiration.

In retrospect, Dagon might not have been the optimal choice of name for a frightening sea god. Next to nothing is known about myths featuring Dagon, but there’s strong evidence the god had nothing to do with the sea at all. He probably started out as a grain and rain god and turned into a war god later. He did, however, have a temple in Ugarit, an ancient port city in northern Syria. In the Bible, he’s mentioned as the god of the Philistines. Samson destroyed Dagon’s temple in Gaza, and the captured Arc of the Covenant was brought to his temple in Ashdod. In Hellenist times — the three centuries preceding Christ — Dagon’s name was in all likelihood transformed to Marnas.

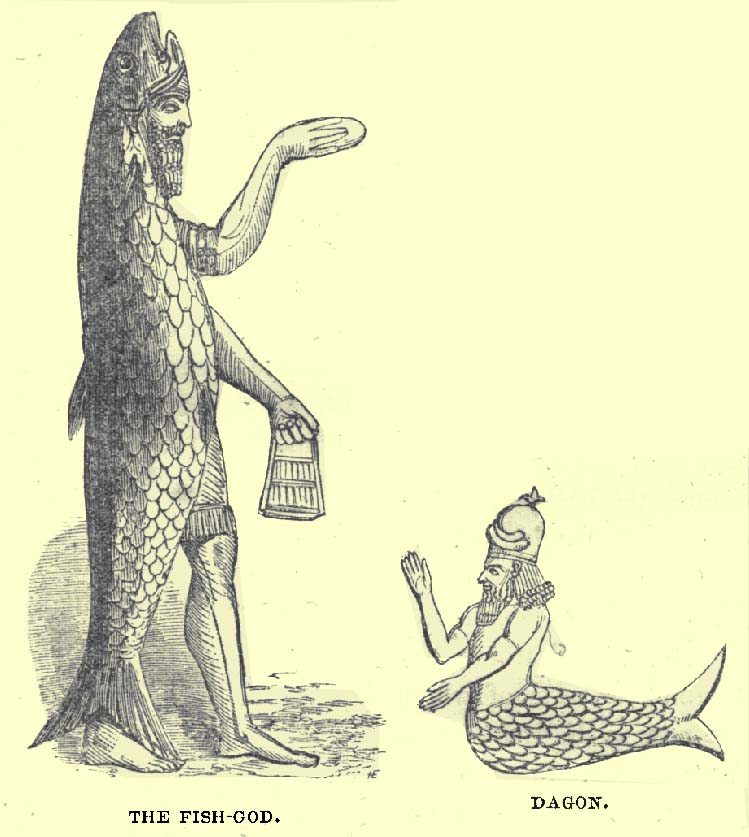

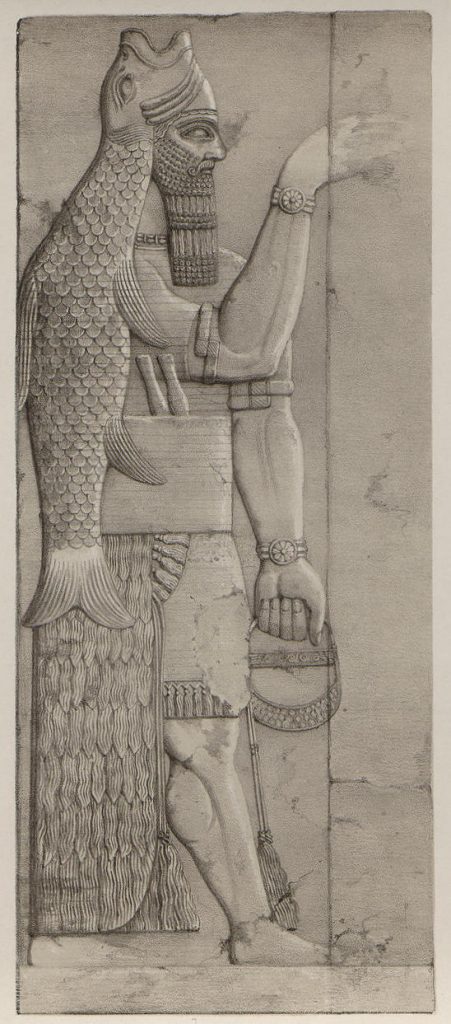

Marna signifies The Lord in Aramaic. He was the principal god of Gaza, who was worshipped well into the 5th century CE. Only in the 13th century, a Jewish Bible commentator wrote that Dagon was half fish and half man. The source of the confusion may lie with the sea-faring Canaanites or Phoenicians who first gave Dagon his fishy attributes because of false etymology: dâg in their language meant fish, and they started depicting Dagon as a hybrid man-fish. Dagon became associated with a Babylonian god from the 4th century BCE, Oannes. Oannes wasn’t a horrible sea god either: he stepped ashore every morning to teach the peoples living in the Persian Gulf written language, the arts, and sciences and then returned to the sea when the sun set. Oannes is in turn associated with the Akkadian Apkallu: seven sages or demi-gods who passed on divine knowledge to the human population, and who were represented as part human and part fish.

Are you still with me? Dagon is a perfect example of how confused and confusing mythology often can be. The ancient gods weren’t fixed in nature. They were derived from sources forever lost to us and underwent various mutations when different cultures came into contact with each other. Gods took over characteristics from gods belonging to other religions. Man wasn’t created by a god; the gods were created by man, and we continuously tinkered with our creations to make them fit our needs. Gods were changed in character and attributes; they were merged with other gods; they took different names in different civilisations and kept evolving. Whatever we think we know about ancient religions is fragmentary at best, and probably wrong on several counts. That creates opportunities to play around with as a writer.

For Dream Whisperer, I decided to stick with Dagon instead of Oannes because of Dagon’s place in the Cthulhu Mythos. I turned him into a creature with humanoid characteristics — he has arms — without making him half man and half fish from the navel down. My Dagon has the head of a monstrous deep-sea fish. When his followers turn up in London to shadow Wheeling, they speak Ugaritic — a wink to the god’s former presence in northern Syria. Holmes and Lagergren track down the Order of Dagon in London through a letterhead featuring an Apkallu figure derived from a bas-relief from the temple of Ninurta at Nimrud.

Is Dagon in Dream Whisperer a bad guy? Well, he thinks political dialogue with mankind is useless, and that makes him our enemy. From his perspective and that of the Deep Ones, he has a point, though. One species’ hero is another’s monster. It’s no different in human history.