In a previous blog, I wrote about Lovecraft’s aversion of the sea. It was obvious right from the start that the sea would have to play an essential role in Dream Whisperer, and so it does. The two main heroes in the novel have opposite views on the watery realm. Fleming shares Lovecraft’s pessimist opinion that nothing good can come from the oceans whereas Dr Rebecca Mumm, a marine biologist, positively waxes lyrical about the subject. She even quotes the French symbolist poet Verlaine at her colleague Ove Eliassen: ‘La mer est plus belle que les cathédrales’ — ‘The sea is lovelier than the cathedrals’. Debussy used the poem as lyrics for a song. The protagonists’ disagreement typifies two different attitudes: the atavistic fear of the unknown versus the excitement associated with the prospect of discovering new things.

Although I personally share Rebecca’s positive attitude, the sea is a continuous source of horror in Dream Whisperer. The first team sent out to destroy a ‘Sleeper site’ — a spot where a sleeping Cthulhu resides — has to confront aggressive mermen and mermaids. Their mission leads them to Pulau Balambangan in current-day Malaysia, off the northern tip of Borneo. I was attracted to the region because Borneo was a fertile source of inspiration for late-19th-century popular fiction featuring jungle adventures and pirates. I was browsing the internet to find information about local myths I might use and hit upon a short amateur video on YouTube about a ‘dead mermaid at Balambangan island’ — it’s still easy to google. The low-quality film is an obvious hoax, but it inspired me to select the island as a location for my novel.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NkpZ84g7M3s

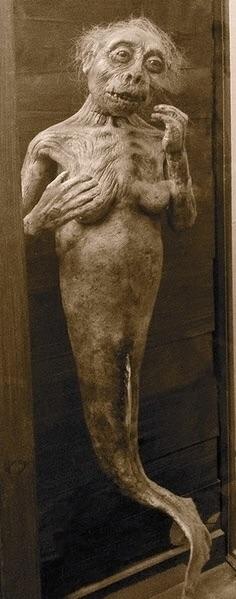

When Rebecca later discusses the event, she refers to the merman in the collection of the Horniman Museum. The museum is in Forest Hill in the south of London. It opened in 1890 and was the result of the tea merchant and MP Frederick Horniman’s enduring collecting frenzy. I had the pleasure of visiting this wonderful place several years earlier and was delighted I could use their creepy merman in my book.

In 2014, the item was subjected to an X-Ray analysis and CT-scans, which laid bare that the little monster of Japanese origin was a concoction of wood, clay, papier-mache, and wire combined with real fish attributes. The Guardian published an interesting article about it.

However, the Horniman Museum isn’t the only place in London with a fake merman on display. They’re also to be found at the British Museum, the Science Museum, and the lesser-known (but interesting) Wellcome Collection. Sir Henry Wellcome acquired no less than three specimens in the early 1900s. I only recently learnt that the ‘monkey-fish’ at the Horniman originally belonged to the Wellcome Collection. It arrived in Forest Hill in 1982, which of course means that the reference to the Horniman in Dream Whisperer is incorrect. We live and learn… Maybe I’ll fix it in the next edition.

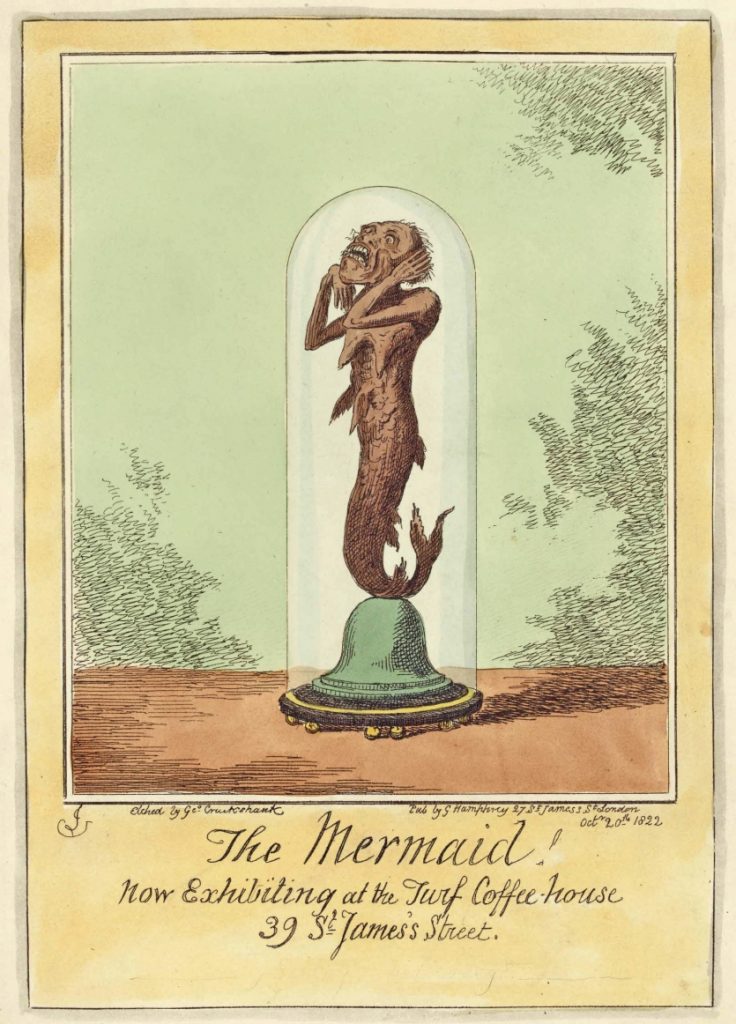

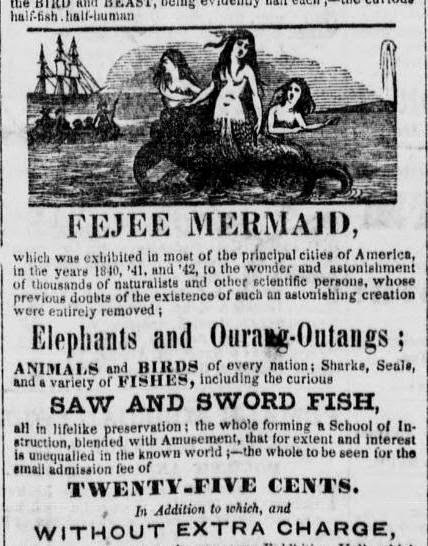

The manufacturing of fake merpeople was a veritable cottage industry in 19th-century Japan and the West-Indies — although the tradition is much older: Specimens from as early as the 13th century are known to exist. They were used in religious ceremonies and amulets. When Japan opened up to the West for trade halfway the 19th century, the ningyo – ‘human-fish’ — found their way to Europe and the US.

They got to be known as ‘Fe(e)jee mermaids’ thanks to the showman and hoaxer P.T. Barnum, who advertised them as ‘bare-chested mermaids’ to excite male curiosity and turned them into a resounding success with the public. Many ‘mermaids’ ended up in museums, which were at that time mixed showcases of the odd and the scholarly. It’s surprising to think that academicians from that period could be gulled into believing these atrocities were indeed authentic taxidermied sea creatures.