In Dream Whisperer, Lady Eiluned, a high-ranking elf and Fleming’s grandmother, tells her grandson that the elves have decided to leave Earth because there’s no future for them in our world.

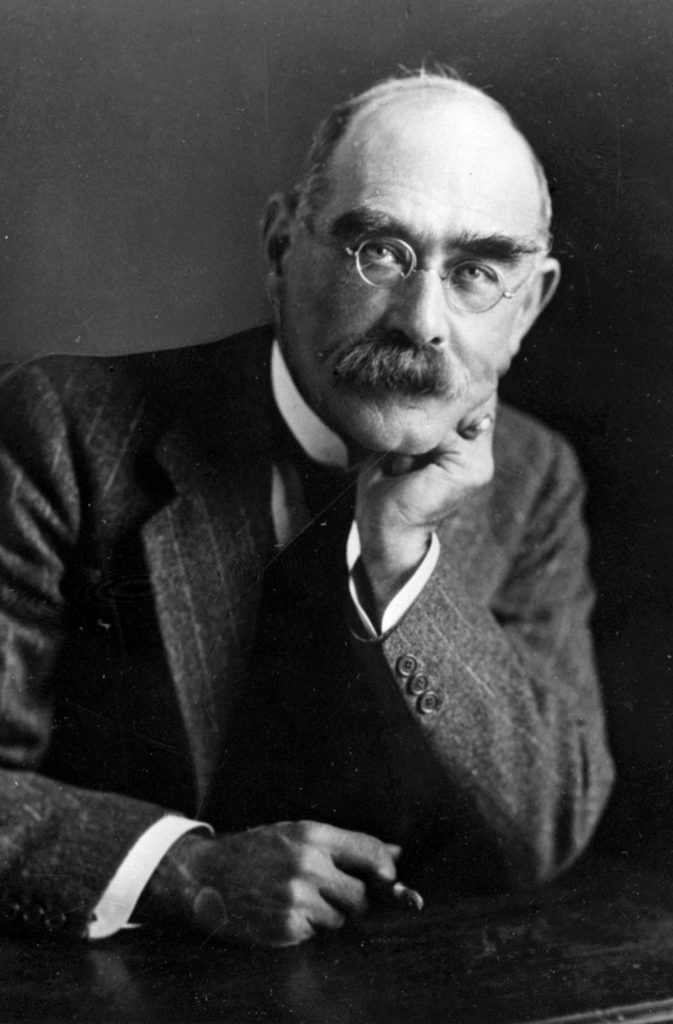

About forty years ago — yes, I’m ancient — I went through a Kipling phase. I read all of his novels and short stories and enjoyed most of it a lot. I know, liking Kipling isn’t fashionable. It isn’t even politically correct. The man was a bullhorn for British Imperialism, and his jingoistic attitude wouldn’t be acceptable today — maybe somebody should tell that to Bojo and his deluded gang of Brexiteers. But the man knew how to tell a story.

In Puck of Pook’s Hill, he conjures up Puck in a rural Sussex meadow — ‘a fairy ring of darkened grass’ — where two children, Dan and Una, rehearse Midsummer’s Night Dream. The sprite tells them stories and introduces them to historical characters. At the end of each tale, he gives the children a leaf of ash, oak, and thorn to make them forget what they’ve seen. In the first story, Weland’s Sword, Puck reveals to the children that the hills are empty. The People of the Hills are all gone. They’ve left Britain:

‘The People of the Hills have all left. I saw them come into Old England and I saw them go. Giants, trolls, kelpies, brownies, goblins, imps; wood, tree, mound, and water spirits; heath-people, hill-watchers, treasure-guards, good people, little people, pishogues, leprechauns, night-riders, pixies, nixies, gnomes, and the rest—gone, all gone!’

Puck dislikes the words elf or fairy. He tells the children that those words refer to travesties of what the People of the Hills really were:

‘Can you wonder that the People of the Hills don’t care to be confused with that painty-winged, wand-waving, sugar-and-shake-your-head set of impostors? Butterfly wings, indeed! (…) The fact is they began as Gods. (…) (They) insisted on being Gods, and having temples, and altars, and priests, and sacrifices of their own. (…) But what was the result? Men don’t like being sacrificed at the best of times; they don’t even like sacrificing their farm-horses. After a while, men simply left the Old Things alone, and the roofs of their temples fell in, and the Old Things had to scuttle out and pick up a living as they could.’

In a couple of sentences, Kipling summarises what happened to most pre-Christian deities in Britain and Ireland. Christian monks turned the pagan gods who didn’t make it as saints or mythical heroes into malevolent demons, which evolved, over the years, into small, mischievous night creatures, living under ‘the hills’ — the pre-historical burial mounds — of the British Isles. In Victorian times, they were sugar-coated into even smaller, gauzy-winged, delicate creatures, flitting amongst the flowers in English gardens. Peter Pan’s Tinker Bell is a late example of that trend. 19th-century Britain was obsessed with fairies, not just in children’s stories, but also in paintings. Even intelligent people, like Arthur Conan Doyle, could be goaded into believing they actually existed. In Dream Whisperer, Mycroft Holmes still revels in the hoax he played on the author he so dislikes.

The transformation of the gods into the People of the Hills is first described in the mythical history of Ireland, the 12th-century Lebor Gabála Érenn — better known as The Book of Invasions in English. The fifth race to invade the Irish shores was the Tuatha Dé Danann, Ireland’s pagan gods, which were then defeated by the Milesians, the Gaels. After their defeat, the gods retired under the hills and lost their formidable aspect over centuries of Christian dominion. It took a scholar of J.R.R. Tolkien’s calibre to rehabilitate the elves — not quite as the gods they initially were but as human-sized, fierce warriors.

So, the Fleming universe draws both from the insights of modern comparative mythology and Kipling’s statements. Some of the gods decided to make a living amongst humans, leading unremarkable lives, whereas the People of the Hills chose to leave Earth. It’s early days, but I intend to explore that departure in some greater detail in the third book in the series. So expect more on this subject in this blog later on.